Secrets of Success: How EPI-Q Does Real-World Research Really Well

May 22, 2014

I recently conducted a podcast with Dr. Mark Jewell, President of EPI-Q, about his Secrets to Success in designing and conducting real-world evidence (RWE) research studies for the pharmaceutical and healthcare industry.

Why EPI-Q? Two main reasons:

- EPI-Q has conducted hundreds, if not thousands, of healthcare studies representing tens of thousands of patients over the past two decades.

- EPI-Q has worked with an incredible diversity of providers and patient-care environments in these studies, thus gaining extensive insight into how to conduct research in various arenas.

EPI-Q’s RWE studies have produced results which have been widely published not only in peer-reviewed literature, but these results have gained world-wide attention and have influenced health policy. Their study results have been discussed on CNN, CBS News, US News and World Report, among others.

A summary of my interview with Dr. Jewell is below, or you may listen to the podcast here to benefit from his “in the trenches” experience with successfully conducting real-world research.

- What is the level of evidence required?

- When are results needed?

- Who is the internal audience within the client sponsor?

- Who is the external audience?

- What business objectives are you trying to accomplish?

Then, one needs to delve deeper and this is where we typically uncover the real challenges – the major “learnings”, so to speak. For example, as researchers, we:

- Clarify study objectives;

- Seek collective buy-in from internal key stakeholders;

- Identify specific audience segments for the results; and,

- Further elucidate exactly what will resonate with these individual audiences.

Through this process, we begin to operationalize exactly how to answer these questions, allowing the development of the specific methodology for the study.

[PP] What processes have you used when working in a therapeutic area or a product that currently is of low awareness or interest to the payer or your target audience?

[MJ] We have absolutely encountered this challenge, and we’ve approached it in a few innovative ways! A case study is a good way to explain this.

We had a client with a product for insomnia. The Phase III clinical trial data were quite promising from a clinical perspective; however, payers had indicated that insomnia was a disease state lacking in importance to them. Insomnia was just not on their horizon, although it was a prevalent condition.

In addition to low awareness and interest, a complicating factor was that the definition of insomnia was varied. This resulted in wide-ranging estimates of prevalence in the published literature.

The combination of these awareness and disease state definition issues suggested that a typical RWE study would not generate evidence that would result in favorable positioning for the company’s product. However, we still needed to create a product value message that was meaningful to relevant stakeholders.

Our solution was multi-fold. We first began with evaluating the type of data that could be used to accurately establish burden of illness for insomnia to various customer groups, including a newly-identified audience – the employer. Through this process, we determined that employer-relevant data such as absenteeism and presenteeism associated with insomnia would not be typically available in traditional claims databases.

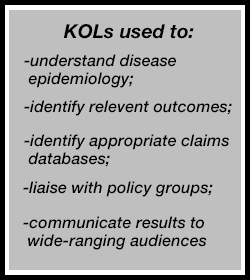

This led us to establish a relationship with key opinion leaders (KOL) and other relevant stakeholders who

- Refining the definition of the disease;

- Assessing the epidemiology of insomnia using robust data; and,

- More fully quantifying the burden of insomnia from various perspectives.

One KOL served as the principal investigator (PI) and assisted with identifying potential claims databases that would allow us to quantify many of our economic outcomes. In addition, these KOLs would eventually serve as allies and experts in the transmission of the study results to relevant external groups, an activity I’ll describe in more detail later in the interview.

Through this process of establishing the research objectives from various perspectives, we also identified the need to quantify the disease burden utilizing patient-reported outcomes (PRO), including absenteeism and productivity-related effects. Therefore, our research protocol utilized a combined strategy whereby we used a claims database plus PROs obtained through interviews with a segment of the population to provide a complete picture of the burden of illness associated with insomnia.

Lastly, we encountered another challenge in this particular study, this one relating to study data control. We found that the owners of the claims database that we had originally identified wanted to maintain control of their data and the study results. However, this did not fit with the original objectives as identified by the sponsor. We handled this by engaging our PI who collaborated with us to define the study objectives, design, and database identification. This PI helped achieve a solution that allowed both access to the data and a mutually acceptable control of results.

I like to describe this insomnia case study because I believe it highlights the many roles that can be played by a KOL/thought-leader in real-world evidence studies. In addition, this research project showcases how to identify what data are important, processes we went through to obtain the data and how long it takes to get it, as well as it describes the different partners that an organization needs to work with in order to address relevant stakeholder issues during the study and after the results are available.

(Editor Note: For access to EPI-Q’s publications and other work related to insomnia, visit here.)

[PP] What are some lessons learned when EPI-Q has worked with some of the newer organization types such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) or Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs)?

[MJ] There are many advantages to working with ACOs and IDNs, and particular types of data (such as hospital readmissions, among others) resonate strongly with payers. So, these relationships with ACOs and IDNs, and the utilization of their data for research, are very useful.

But there are some important factors to consider when working with these groups because their main job is patient care, not research or data provision. These issues have a direct effect on timing and budget. For example, they may not have an Investigational Review Board (IRB), and we’ve found that we may need to liaise with many different types of individuals in order to build relationships to achieve political support to conduct the research, access the data, identify processes, etc. Instead of the IRB, a Medical Director of a therapeutic area may be in charge, or someone in Quality Management or Improvement handles such studies. On occasion, they may have a senior level individual in charge of Research, and we need to work with this group.

These relationships with the internal groups just mentioned are very important as you navigate the organization’s Legal Department. Legal may have standards of practice as they relate to clinical research studies (such as obtaining informed consent), but these are not necessary or appropriate for observational research, for example. With internal relationships already established with individuals like those I identified, then it is easier to negotiate research protocols within the organization. We’ve also encountered the need to present the study to an initial committee (before it goes to an IRB), and this preliminary review assesses if the study has scientific merit of it’s appropriate or relevant for the ACO or IDN.

These groups are extremely important from a strategic perspective, but it is essential to understand that working with ACOs or IDNs may affect study timing and budget (as already mentioned), but it may also directly affect research methodology. Nevertheless, working with these groups is increasingly essential for our industry.

[PP] When you look across the vast array of data sources available, what qualifying criteria do you use for your research studies?

[MJ] We start, of course, with the individual objectives of the study. Then we assess whether the data source is representative of the study or target population, is it sufficient in size to provide enough study patients, is there sufficient quality to the data, does it have the appropriate and necessary data elements, and can we have the desired control over the data. Again, let me use a case study to showcase some real-life examples that can be encountered when selecting the best data source.

In one example, we had a client that desired to evaluate treatment outcome differences between their product and a competitor in the relatively rare chronic kidney disease population. As we investigated data sources, it was essential that the database have a sufficient number of patients with the identified disease (and with patients taking the identified treatments), and the data source needed to provide generalizability and sufficient internal validity. We found no single database that fulfilled these basic criteria.

We determined the need to combine up to four separate databases, and beyond the challenges of combining disparate data sources, we encountered – again – the challenge of who controlled the data if portions were owned by four separate groups. EPI-Q, as a 3rd party, acted as a mediator between these four groups and the sponsor, identifying a process for data combining and sharing, which eventually led to a successful study, and peer-reviewed presentations and publications. Results from this chronic kidney disease RWE research can be viewed here.

Challenges like these are common in RWE study design, and this case study shows an effective means to resolve operational and study design issues, in a collaborative effective fashion.

[PP] Since all databases have one or more pieces of information that are missing, incomplete, or insufficient, can you summarize some methods you’ve used to supplement these claim sources with other methods.

[MJ] We have used claims combined with interviews collecting patient-reported outcomes (e.g., the insomnia study). We have several examples of using a 3-prong approach, including supplementing administrative claims with electronic medical records (EMR) plus chart review, conducted on a subset of the population (to derive diagnostic test data that were not available in the claims or the EMR data). And we have used claims data plus EMR, but did not have sufficient money for interview data or chart review, so we conducted an on-line survey with patients derived from the specific plan population (in one study) or from the US population (in another study). A detailed case study can be viewed here.

[PP] Health Outcomes Liaisons (HOLs) are increasingly being deployed by industry as an important group who interacts directly with payers. How does EPI-Q work directly with HOLs in the research process to understand what customers want in the RWE studies?

[MJ] Health Outcomes Liaisons are eager to use data from RWE studies because it allows them to talk with stakeholders in meaningful ways beyond just sales data. It facilitates a peer to peer interaction, and helps the HOL to better understand their customer (and, in some cases, the payer better understanding their own patient population) in terms of treatment and medication trends, usage patterns, as well as costs and resource utilization.

RWE data are useful for payers in terms of creating benchmarking reports, treatment reports, and publications addressing cost and quality issues, among others. It is always imperative to work closely with the sponsor’s compliance, legal, regulatory, and other departments in terms of developing these materials for use in the field. But there is a lot of evidence of success with the use of RWE data with major customer groups, and EPI-Q has a good deal of experience in working closely with these customer-facing groups.

[PP] Let’s take a 20,000 foot view. What changes have you seen in real-world evidence research over the past few decades?

[MJ] Oh there have been many good changes! I believe we are much more thoughtful on how RWE data are used, and we have a better understanding that real-world evidence is not a magic bullet. We accept that there are limitations, and as such, we’ve gotten better at identifying whether and when RWE is appropriate.We’ve also gotten much better at learning how to give life to the RWE study results on the back-end of the research project, meaning how to use RWE data and all the different groups that it can affect and influence, beyond providers and payers. For example, RWE can be utilized with patient advocacy groups, with CMS for the Five-Star Quality Rating System, it can inform performance measures such as HEDIS, as well as being used to tie observational research results into reimbursement arrangements with payers. These other uses of RWE are extremely important to consider early in the process, when you are setting up the study design, so that the most impact can be gained from the study results.

We’ve also improved at knowing where to conduct the studies (i.e., in what environment), such as whether ACOs or IDNs are relevant based on whether the study has important outcomes such as hospital readmission issues or the intervention under study has specific reimbursement challenges.

In terms of using RWE with advocacy groups or professional organizations, I’m not suggesting using it for undue influence, but rather working with these groups so that they are aware of the data coming out, and can utilize the data, if appropriate, for their initiatives. The insomnia study is an example of this. Our KOL worked closely with members of policy-making bodies so that they had the data for use in DSM-V and ICD-10 to redefine thresholds of treatment, and for crafting the definition of insomnia to determine prevalence. We were very proud that these groups utilized our study data for policy-making purposes.

At EPI-Q, we are very excited about our two decades of experience with RWE and the future opportunities that exist for finding even more impactful uses of the data, including developing patient decision aids, shared decision-making tools, diagnostic and treatment guidelines, quality initiatives, reimbursement, and more. You can find out more about EPI-Q and our research by visiting our website (https://www.EPI-Q.com) or contacting us by telephone at (630) 570-5505.